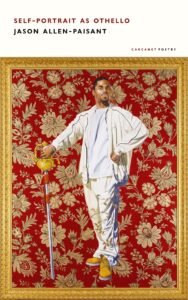

La seconda raccolta del poeta e accademico giamaicano Jason Allen-Paisant per Carcanet, successiva a Thinking with Trees del 2021, è una meditazione intensa e potente su identità, assenza, perdita, linguaggio, arte e rappresentazione. Frasi e immagini si susseguono nelle poesie, generano energie e schemi tematici e linguistici che attraversano tutte e tre le sezioni del volume e ci invitano a creare connessioni tra di esse e a farle dialogare.

Oltre a quella di Otello, le figure della ‘Mama’ (o della nonna), della madre e del padre assente – o ‘NO-DAD’ (‘SENZA PAPA’) o ‘Un-Dad’ (Non Papà), come lo chiama in modo toccante – sono presenze che il poeta percepisce mentre trova la sua strada per l’Europa, frequentando l’École normale supérieure a Parigi, visitando Venezia e Praga e facendosi trasportare su un punt[1] lungo il fiume Cherwell a Oxford prima di ritornare in Giamaica.

All’inizio della raccolta Allen-Paisant allude a Baudelaire e c’è qualcosa del flâneur nel personaggio lirico che attraversa questi spazi cosmopoliti, ma anche liminali, che è nel contempo in quei luoghi, ma non appartiene a essi, come quando, in « una stanza umida al terzo piano/ École normale supérieure/ nessun altro suono in quel corridoio se non nel mio sangue », avverte « quanto la solitudine tagli di netto il corpo » e « sarò sempre uno straniero qui il punto è il cazzo di/ punto è che non l’avevo capito/ non avevo capito che il nero fosse un’altra lingua ».

O ancora nella poesia rivolta al padre assente che chiude la prima sezione e inizia con “Mi siedo al barbecue* mentre l’acqua scorre libera nella vasca”, che, nella tessitura o nella giustapposizione di motivi già introdotti, assume un tono più provocatorio, persino celebrativo, quando il poeta si mette « in cammino, ballando tra Praga Parigi Roma » e « saltellando fino a Oxford ». Lo « straniero qui » subisce una metamorfosi, facendosi invece « attore e spettatore di un carnevale di corpi », non lasciando che « tutta la bianchitudine » e « tutti i discorsi snob mi disturbino », e infine « alzandomi in piedi,/ pronto a correre, a frenare. Chi sono diventato ora lo devo a me stesso ».

Se le poesie della prima sezione possono essere lette come un rito di passaggio, quelle della seconda allargano e approfondiscono la prospettiva, in primo luogo attraverso l’impegno di Allen-Paisant verso Otello o “Ciò che Shakespeare non scrisse. La storia che non fu in grado di narrare”, come dice lui stesso, ma anche la storia della tratta degli schiavi e le percezioni e rappresentazioni del corpo dei neri nell’arte europea. Molte delle poesie di questa sezione hanno la natura esplorativa ed estrattiva della scrittura ecfrastica e psicogeografica, che dissotterra e decifra anomalie, dettagli, struttura dei sentimenti, impieghi linguistici e una « negoziazione infinita » del sé, della storia e della cultura – « negoziazione infinita » che costituisce le economie simboliche in cui ci troviamo, appena fuori o nei limiti precari. Come recita la poesia “Autoritratto in veste di Otello II”:

Cosa significa essere molto più bianco che nero?

Istruzione parlata abbigliamento cultura. Avere la forza

di volontà di un bulletto geniale più tenace

nei lavori di testa che di mano. Conoscere la

strada vivere rasta parlare shakespeariano

baudelairiano dantesco e nietzchiano parlare sound systemese.

Qual è in realtà la tua lingua d’origine?

Queste poesie hanno qualcosa di ricco e denso che, sebbene Allen-Paisant dispensi sapere con leggerezza, fanno riecheggiare l’idea di un intreccio di culture, di un’autentica intertestualità post-moderna.

La sezione finale, più breve, ritorna a una voce più personale, poesie sul ritorno a casa, sulla perdita personale, e una brevità alla maniera di William Carlos Williams in quella conclusiva, intitolata semplicemente “Giamaica”, in cui Allen-Paisant raffigura l’isola attraverso la sensazione fisica del gusto – dell’accento, del villaggio rosso, della saponata che si asciuga, ma

soprattutto

sapore

di cose che il sole

fa evaporare [2].

È un’immagine che incarna in modo appropriato la precarietà e l’ambiguità che infestano il resto della raccolta, in cui le vulnerabilità e la passione di scoprire e capire si combinano con un abile e duttile spaziare attraverso i registri del linguaggio che rendono l’opera importante e, soprattutto, multistrato e coinvolgente.

Traduzione di Emanuela Chiriacò

* In Giamaica, la grande struttura in pietra, piatta e leggermente inclinata, su cui viene essiccato il caffè, è chiamata barbecue, come spiega il poeta nelle Note alla fine del libro.

[1] Tipico barchino di Oxford e Cambridge condotto con una pertica.

[2] La traduzione dei presenti versi della poesia “Giamaica” è a cura di Andrea Sirotti.

Recensione originale:

Self-portrait as Othello Jason Allen-Paisant (Carcanet Press, 2023)

Reviewed by Tom Phillips

The poet and academic Jamaican Jason Allen-Paisant’s second collection for Carcanet following 2021’s Thinking with Trees is a concentrated and powerful meditation on identity, absence, loss, language, art and representation. Phrases and images loop through these poems,generating thematic and linguistic patterns and energies that course through all three sections of the book and invite us to make connections between them and bring them into conversation with each other.

In addition to that of Othello, the figures of Mama (or grandmother), mother and an absent father –or ‘NO-DAD’ or ‘Un-Dad’ as he is poignantly referred to – are felt presences as the poet negotiates his way through Europe, attending the École normale supérieure in Paris, visiting Venice and Prague and being punted along the Cherwell river in Oxford before making a return visit to Jamaica.

Early on in the collection Allen-Paisant alludes to Baudelaire and there is something of the flaneur about the lyric persona who passes through these cosmopolitan, but also liminal spaces, simultaneously in such places, but not of them, as when, in ‘a damp room on the third floor/École normale supérieure/no sound in that hallway but in my blood’, he senses ‘how sharply loneliness cuts the body’ and ‘I will always be a stranger here the thing is the bloody/thing is I didn’t realize it didn’t/realize that Black was a different language’.

Or again in the poem addressed to his absent father that closes the first section and begins ‘I sit on the barbecue* when the bath water pour’, which, in weaving together or juxtaposing motifs he has already introduced, assumes a more defiant, even celebratory tone as the poet sets out on ‘a doing road, dancing through Prague Paris Rome’ and ‘bouncing up into Oxford’. The ‘stranger here’ undergoes a metamorphosis, becoming instead ‘actor and spectator in a carnival of bodies’, not letting ‘all the whiteness’ and ‘all the posh talking bother me’, and finally ‘rising standing up straight,/ready to run, to bound. What I am now stands on its feet’.

If the poems in the first section might be read as a rite of passage, those in the second broaden and deepen the perspective, primarily through Allen-Paisant’s engagement with Othello or ‘What Shakespeare did not write about. The story he was unable to tell’, as he puts it, but also with the history of the slave trade and perceptions and representations of the Black body in European art. Many of the poems in this section have the exploratory, excavatory nature of both ekphrastic and psychogeographical writing, unearthing and puzzling at anomalies, details, structures of feeling, language deployments and the ‘endless negotiation’ of the self, history and culture – the ‘endless negotiation’ that constitutes the symbolic economies we find ourselves in, just outside of or on the precarious limits of. As the poem ‘Self-Portrait as Othello II’ has it:

What does it mean to be far more fair than black?

Education speech dress learning. You have the brawn

of intellectual rude boy sturdier in brain-work

than in war. Know streets and livity talk Shakespeare

Baudelaire Dante and Nietzche talk sound system. What

actually is the language of where you’re from?

There is something rich and dense about these poems which, although Allen-Paisant deploys their learning lightly, resonates with a sense of interwoven cultures, an authentic post-modern intertextuality.

The shorter final section returns to a more personal voice, poems of homecoming, personal loss and the William Carlos Williams-like brevity of the final poem of all, called simply ‘Jamaica’, in which Allen-Paisant figures the island through the physical sensation of taste – of accent, of red village, of soap sud drying, but

above all

taste

of things sun

boils away.

It’s an image that fittingly embodies the precarity and ambiguity that haunt the rest of a collection in which vulnerabilities and a passion to tease out and understand combine with an adroit and supple ranging across the registers of language to make it a major and, above all, multi-layered and engaging piece of work.

*In Jamaica, the large, flat, gently sloping stone structure on which coffee is dried is called a barbecue.