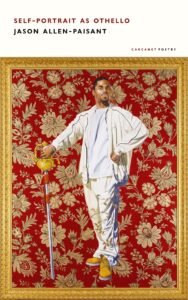

The poet and academic Jamaican Jason Allen-Paisant’s second collection for Carcanet following 2021’s Thinking with Trees is a concentrated and powerful meditation on identity, absence, loss, language, art and representation. Phrases and images loop through these poems,generating thematic and linguistic patterns and energies that course through all three sections of the book and invite us to make connections between them and bring them into conversation with each other.

In addition to that of Othello, the figures of Mama (or grandmother), mother and an absent father –or ‘NO-DAD’ or ‘Un-Dad’ as he is poignantly referred to – are felt presences as the poet negotiates his way through Europe, attending the École normale supérieure in Paris, visiting Venice and Prague and being punted along the Cherwell river in Oxford before making a return visit to Jamaica.

Early on in the collection Allen-Paisant alludes to Baudelaire and there is something of the flaneur about the lyric persona who passes through these cosmopolitan, but also liminal spaces, simultaneously in such places, but not of them, as when, in ‘a damp room on the third floor/École normale supérieure/no sound in that hallway but in my blood’, he senses ‘how sharply loneliness cuts the body’ and ‘I will always be a stranger here the thing is the bloody/thing is I didn’t realize it didn’t/realize that Black was a different language’.

Or again in the poem addressed to his absent father that closes the first section and begins ‘I sit on the barbecue* when the bath water pour’, which, in weaving together or juxtaposing motifs he has already introduced, assumes a more defiant, even celebratory tone as the poet sets out on ‘a doing road, dancing through Prague Paris Rome’ and ‘bouncing up into Oxford’. The ‘stranger here’ undergoes a metamorphosis, becoming instead ‘actor and spectator in a carnival of bodies’, not letting ‘all the whiteness’ and ‘all the posh talking bother me’, and finally ‘rising standing up straight,/ready to run, to bound. What I am now stands on its feet’.

If the poems in the first section might be read as a rite of passage, those in the second broaden and deepen the perspective, primarily through Allen-Paisant’s engagement with Othello or ‘What Shakespeare did not write about. The story he was unable to tell’, as he puts it, but also with the history of the slave trade and perceptions and representations of the Black body in European art. Many of the poems in this section have the exploratory, excavatory nature of both ekphrastic and psychogeographical writing, unearthing and puzzling at anomalies, details, structures of feeling, language deployments and the ‘endless negotiation’ of the self, history and culture – the ‘endless negotiation’ that constitutes the symbolic economies we find ourselves in, just outside of or on the precarious limits of. As the poem ‘Self-Portrait as Othello II’ has it:

What does it mean to be far more fair than black?

Education speech dress learning. You have the brawn

of intellectual rude boy sturdier in brain-work

than in war. Know streets and livity talk Shakespeare

Baudelaire Dante and Nietzche talk sound system. What

actually is the language of where you’re from?

There is something rich and dense about these poems which, although Allen-Paisant deploys their learning lightly, resonates with a sense of interwoven cultures, an authentic post-modern intertextuality.

The shorter final section returns to a more personal voice, poems of homecoming, personal loss and the William Carlos Williams-like brevity of the final poem of all, called simply ‘Jamaica’, in which Allen-Paisant figures the island through the physical sensation of taste – of accent, of red village, of soap sud drying, but

above all

taste

of things sun

boils away.

It’s an image that fittingly embodies the precarity and ambiguity that haunt the rest of a collection in which vulnerabilities and a passion to tease out and understand combine with an adroit and supple ranging across the registers of language to make it a major and, above all, multi-layered and engaging piece of work.

*In Jamaica, the large, flat, gently sloping stone structure on which coffee is dried is called a barbecue.